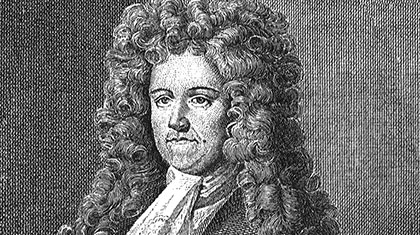

[ABOVE—Daniel Defoe, from Walter Besant’s London in the time of the Stuarts [from an engraving in the British Museum] (Adam and Charles Black, 1903)]

Daniel Defoe is best known as the author of Robinson Crusoe, Moll Flanders, and A Journal of the Plague Year. These fictions capture the Puritan interest in the progress of the soul toward repentance. Defoe was also a religious dissenter (one who rejected the established church) and a political satirist. (His Review laid the foundation for journalism independent of government sponsorship; he commenced it as a weekly but soon issued it three times a week, and wrote every article himself for nine years). A satire of his, titled, “The Shortest Way with the Dissenters,” landed him in prison and compelled him to appear three times in the pillory. Defoe had extended High Church arguments to a ridiculous and savage length, but the satire was so cleverly written it was seriously accepted by both sides, until exposed as a hoax. The national fury was intense.

History of Christianity is a six part survey designed to stimulate your curiosity by providing glimpses of pivotal events and persons in the spread of the church.

While in prison, Defoe published several works, including a pamphlet calling Dissenters to acknowledge the value of the national church and the national church to grant full tolerance to Dissenters. Along with this, and perhaps with the intent to draw the sting from his punishment, Defoe published his “A Hymn to the Pillory.” He was something of a hero with the crowd so that, it is said, instead of hurling at him the customary stones and rotten eggs, they pelted him with flowers. Consequently, it was the government, not himself, that was shamed. Below is an excerpt from his verses on the occasion.

Excerpts from “A Hymn to the Pillory”

…Actions receive their tincture from the times,

And as they change, are virtues made or crimes.

Thou art the state-trap of the law,

But neither can keep knaves nor honest men in awe;

These are too hardened in offence,

And those upheld by innocence.How have thy opening vacancies received

In every age the criminals of state!

And how has mankind been deceived

When they distinguish crimes by fate!

Tell us, great engine, how to understand

Or reconcile the justice of the land;

How Bastwick, Prynne, Hunt, Hollingsby, and Pye,

Men of unspotted honesty,

Men that had learning, wit, and sense,

And more than most men have had since,

Could equal title to thee claim

With Oates and Fuller, men of later fame:

Even the learned Selden saw

A prospect of thee through the law:

He had thy lofty pinnacles in view,

But so much honor never was thy due:

Had the great Selden triumphed on thy stage,

Selden, the honor of this age,

No man would ever shun thee more,

Or grudge to stand where Selden stood before.Thou art no shame to truth and honesty,

Nor is the character of such defaced by thee

Who suffer by oppressed injury.

Shame, like the exhalations of the sun,

Falls back where first the motion was begun;

And they who for no crime shall on thy brows appear,

Bear less reproach than they who placed them there…